This post is also available in: Deutsch (German)

This article dives into multimodal public transport and routes that make or break multimodal transport.

Multimodal transport is common if you think about it

Imagine any one of these scenarios:

You cycle to the bus stop, catch a bus to the train station, take a train to the stop connected to a mall next to your office and walk through the mall with a bicycle by your side to reach the office for work.

You walk to the train station next to your apartment to take a train to an interchange station, from which you walk to another train line to catch a train that leads you to the station where you need to take a bus, ride to a bus stop and walk for about 10 minutes from the bus stop to your university.

You book a taxi using an e-hailing app to fetch your butt and your luggage from your house to a nearby train station that has a train line that goes straight to the airport. You board the flight to your destination, get off the plane and book another taxi to ride to the hotel of your choice.

The product you ordered from an international online store was shipped from the product’s country of origin to your country’s harbour and then delivered to your doorstep either by van, car or motorcycle.

These scenarios are examples of multimodal transport journeys which are relevant for both commute and cargo applications. Multimodal transport refers to the combined use of multiple transport options such as moving by foot, bicycle, taxi, bus, train, aeroplane and car to move from point A to point B.

This is contrary to unimodal transport, which obviously refers to getting from A to B using just 1 mode of transport (for example, driving your own car). But the chances of a transport route being unimodal might be close to nil. You’re actually more likely to take a multimodal route if you’re a public transport user.

Why? According to a 2020 Victoria Transport Policy Institute (VTPI) report by Todd Alexander Litman, most of the transport planning has been car-centric, resulting in well-developed road systems suitable for the movement of cars, but at the expense of the needs of the following non-automobile users:

- Youths who are too young to drive.

- Old people who are too old to drive.

- Disabled adults who cannot drive.

- Lower-income households and individuals who can’t afford to buy a car.

- Drinkers who had too much fun at the pub.

- Anyone without the local driver’s license.

- People who want to avoid driving a car to improve their health by walking or cycling, protect the environment by cutting carbon emissions and reduce congestion on the road.

Hence, multimodal transport accommodates the infinite ways these non-automobile users need to travel without a car or even a pricey taxi ride.

When does a multimodal route become unattractive?

However, most multimodal transport routes can be inconvenient if the following factors of multimodal transport access and convenience are ignored:

- Location and conditions of public transport stations and stops

- Benches and shelters at stops

- Safe pedestrian sidewalks and bicycle lanes connected to public transport

- Crosswalks, pedestrian signals, and sufficient crossing times

- Capacity to carry bicycles on public transport vehicles

- Accessibility and capacity for wheelchairs

- Accessibility and safety for blind passengers

- Parking for bicycles and vehicles at stations and stops

- Availability of bicycle-sharing services

- Coordination of public transport systems

- Informational and navigational support

Anyone who has taken public transport can agree to the pain of multimodal transport routes because of these factors. Let’s imagine this example:

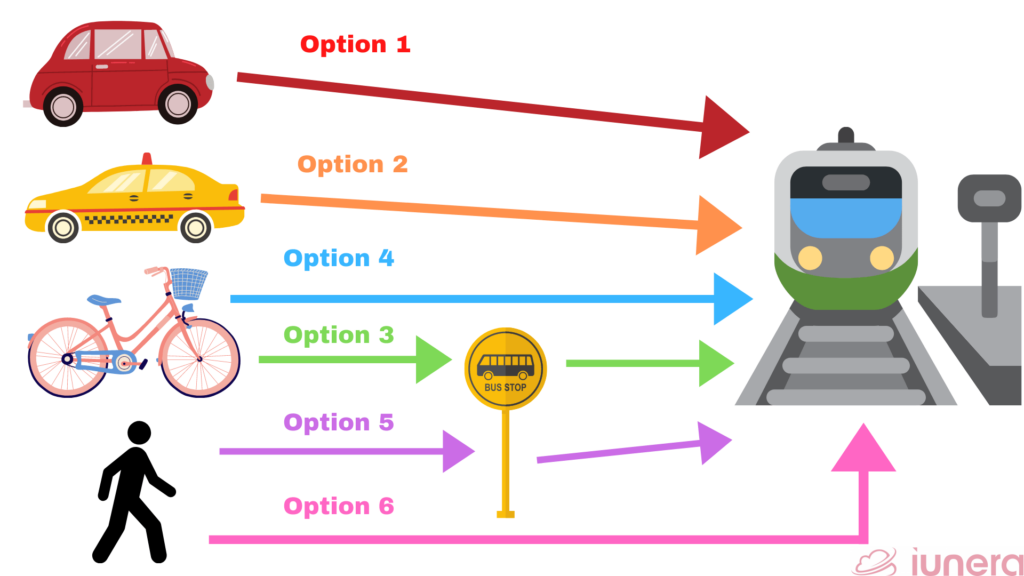

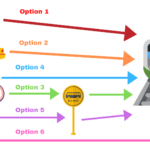

The nearest train station is a 10-minute drive from your house. To reach the train station, you have a few options:

- Drive a car to the train station and park there.

- Book a taxi to the train station.

- Cycle to the bus stop.

- Cycle to the train station.

- Walk to the bus stop.

- Walk all the way to the train station.

Let’s assess each of these options and see which option is optimal.

Option 1

Drive a car to the train station and park there, assuming that the train station has a parking bay. It’s a convenient option since your car will provide much-needed comfort.

But it will only be possible if you have a driver’s license and your own private car, which means that you have money to buy the car. If you cannot afford it, then this option is off the table.

Even if you have a driver’s license and choose to rent a car using a car-sharing (or car rental) app, there are other issues with car-sharing that might put you off, like difficulties in finding a one-way-trip option instead of the round-trip option for this particular journey and the hassle of inspecting the car before using it.

Option 2

Book a taxi to the train station, assuming that you have an e-hailing app on your phone to make the booking. It’s also a convenient option since you get to just sit in the passenger seat and you don’t need to have a car or even a license to drive.

But, due to the high price of any ride, using the e-hailing app daily can add up to a huge chunk of your monthly expenses, so this option is only for those who are willing to add this to their budget.

Option 3

Cycle to the bus stop, wait for the bus and carry your bicycle into the bus to go to the train station. The feasibility of this option really depends on whether there’s a nearby bus stop that is included in your target bus route (i.e., the bus that goes to your target train station). It also depends on whether you have a bicycle and can cycle confidently on the roadside.

It would be safe if there is a dedicated cycling lane but that is not always the case for every cyclist. And also, you’ll have to wait for the bus to arrive at the bus stop or to be careful not to miss the bus, hope there is enough space for your bicycle and carry your bicycle onto the bus. But why go through all that trouble when you might as well cycle all the way to the train station?

Option 4

Cycle all the way to the train station. It’s healthier than Option 3 because you’re pedalling (while balancing) for a longer distance and you don’t have to stress yourself over any bus delays. But you still need to have a bicycle and know how to ride it.

Option 5

Walk to the bus stop, wait for the bus and board the bus to the train station. The feasibility of this option also depends on whether there’s a nearby bus stop that is included in your target bus route.

And you don’t need a bicycle for this. You just have to walk for a certain length of time, depending on the distance of the bus stop from the house. It’s still a healthy option, obviously because it involves some physical activity. But you still have to wait for the bus.

Option 6

Walk all the way to the train station. This option crosses out the need to have any vehicle of some sort and the ability to operate the vehicle or pay for it.

It’s even healthier than Option 5 since you’re not stressing over any bus and you’re walking longer, hence, getting your heart pumping and legs moving for a longer time. But, it would take about half an hour to reach the train station on foot.

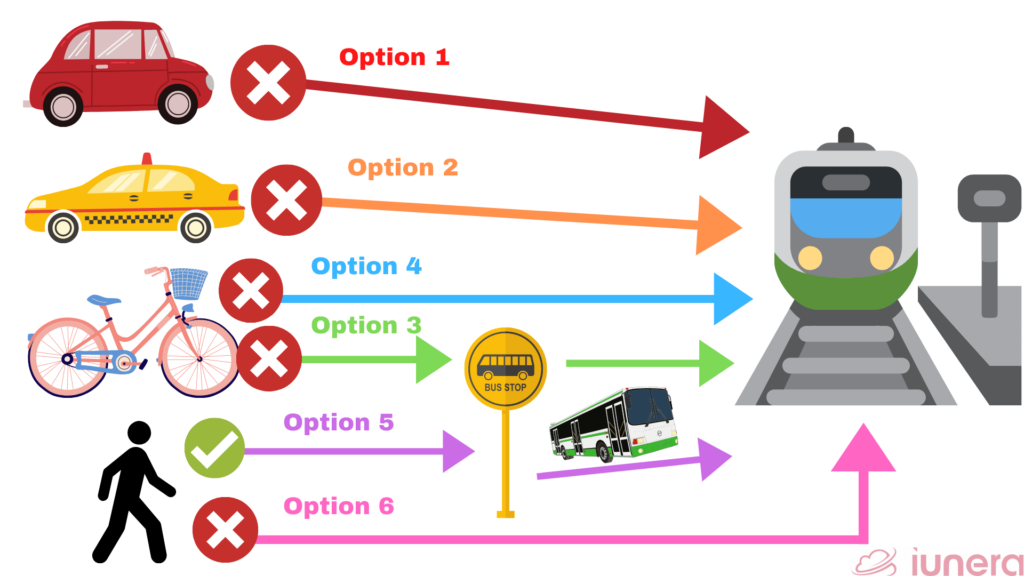

What is your best option?

- Since you don’t have a car, bicycle or access to (or willingness to use) a car-sharing app, you’re cancelling out Options 1, 3, and 4.

- At the same time, you want to optimise your time and money, so Options 2 and 6 are cancelled out. Option 2 is cancelled out because it requires more money while Option 6 is cancelled out because it requires more time.

- So, now you’re left with Option 5, which is to walk to the bus stop, wait and ride the bus to the train station.

Until now, we have assumed that the bus stop and pedestrian facilities are in tip-top condition and that the bus has enough seating space. In reality, however, it’s not always the case.

And now that you’ve held on to your seat on the bumpy bus ride and tapped out of the bus to make your way to the station gates, another public transport challenge awaits you: The possibility of congestion in the train station and the train you manage to board. In other words, the possibility of literally rubbing shoulders, hips and bags with other train passengers.

The challenges of braving the crowds, taking another train line and/or bus route and/or a long walk, tolerating delays (or missing a train/bus) and maybe facing more dilemmas like the one above will go on until you cross the finish line – your final destination. SO STRESSFUL!

Route optimisation

Similar to the example in the previous section, route optimisation is the process of figuring out the most resource-effective routes to move from point A to point B.

With roots tracing back to the travelling salesman problem (TSP) in the 1950s, it’s an algorithmic concept used in transport, logistics and even garbage collection to minimise the time and cost of travelling. The data for route optimisation algorithms can be derived from:

- Satellite data

- Public transport network information

- IoT sensor data

- Mobile data

- Weather forecasts

- Traffic forecasts

Adding to the discussion, a 2013 paper by Jaramillo and Los Gonzalez about route optimisation in public transport presented an optimisation model based on the number of transfers, which is one of the pain points of multimodal transport.

The model attempted to balance the supply and demand decisions:

- Supply decisions about routes and stations. The operators’ objectives are to minimise operating costs and maximise revenues.

- Demand decisions regarding the passengers’ choices of routes which minimise transfers and costs of riding public transport.

However, as the authors themselves noted, this model did not consider the costs of walking to stations or waiting times in order to keep the model simple. That’s why more complex models like the multi-dimensional approach may be more suitable in determining the Pareto-optimal solution.

“Pareto efficiency, or Pareto optimality, is an economic state where resources cannot be reallocated to make one individual better off without making at least one individual worse off.”

Investopedia’s definition of Pareto efficiency or Pareto optimality.

An example of a complex model for public transport is a 2015 paper by Faizrahnemoon, Schlote, Maggi, Crisostomi and Shorten about using the Markov chain to build a multimodal transport network optimisation model. The authors explained that the Markov chain is suitable for big data applications because its properties enable the handling of big data.

The transition matrix of the Markov chain was built using data collected from London’s multimodal transport network and validated using the mobility simulator SUMO (which stands for Simulation of Urban Mobility). A Markov chain-based approach like this can be used to answer questions about improving multimodal transport services such as:

- How easy is it to travel from one part of the city to another?

- Are certain spots accessible in an equitable manner from other parts of the city?

- Are the travel times small between certain bus-stops?

However, there are some challenges getting in the way of analysing and optimising multimodal transport routes including:

- The rural areas are hard to take into account since public transport in rural areas (except school buses) can often be underused and the bus schedules only work on an hourly basis, so using public transport might not even be an option.

- There are different vendors with different sets of data like schedules and vehicle IDs, many of which are not publicly available. This affects the quality of data published on data platforms like the General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS).

- Without an integrated booking or fare payment platform or smart card whereby the fare covers all the transport modes from start to finish for any identifiable passenger, there might be difficulties in obtaining information about the complete journey the passenger makes. Examples of difficulties: passenger’s identity is unknown so the journey is unknown, the walk or bicycle ride is not included in the fare payment platform or smart card, the bus and train tickets have to be bought separately.

- People counting might not be carried out regularly, leading to gaps in daily occupancy data.

- Data privacy concerns come up with certain people counting methods like facial recognition and QR code scans.

Improving the multimodal transport experience

This discussion about optimising multimodal transport routes then begs the question of how transport networks and cities should be planned in such a way that the multimodal transport experience is seamless.

According to the VTPI paper mentioned earlier, multimodal planning refers to transport and land use planning that considers the differing capabilities of different transport modes and land use factors that affect accessibility. The capabilities considered include availability, speed, density, costs, limitations and appropriate uses.

Some notable recommendations for multimodal planning in this paper are:

- Integration of institutions, networks, stations, user info and fare payment systems.

- Quality of connections between and to modes.

- Accommodation of people with special needs.

- Use of comprehensive transport models that consider multiple modes, traffic implications and mobility management strategies like price changes, service quality improvements and land-use changes.

- And the best recommendation of all:

“People involved in transportation decision-making (public officials, planning professionals and community members) should live without using a personal automobile for at least two typical weeks each year that involve normal travel activities (commuting, shopping, social events, etc.) in order to experience the non-automobile transportation system.”

Written by Todd Alexander Litman, Victoria Transport Policy Institute, 2020.

Yes, transport and urban planners need to put themselves in the shoes of the public transport users if they truly want to learn how they should be designing the infrastructure.

Ultimately, urban planners generally need to start building better cities by following these 7 universal principles coined by urban designer Peter Calthorpe:

- PRESERVE: Preserve natural ecologies, agrarian landscapes and cultural heritage sites.

- MIX: Create mixed-use, mixed-age group and mixed-income neighbourhoods.

- WALK: Design walkable streets and human scale neighbourhoods.

- BIKE: Prioritise bicycle networks and auto-free streets.

- CONNECT: Increase density of road network and limit the block size.

- RIDE: Develop high-quality and affordable public transport services.

- FOCUS: Match density and mix to transport capacity.

In its essence, better cities are the ones that aim to reduce the dependency on car usage and improve the quality of life for everyone, including those without a car.

Takeaway

What is multimodal transport?

How is multimodal transport different from unimodal transport?

Unimodal transport refers to getting from A to B using just 1 mode of transport.

Multimodal transport involves more than 1 mode of transport.

Why are multimodal routes so common in public transport?

Who are the non-automobile users?

- Minors.

- Senior citizens.

- People with disabilities.

- People who can’t afford to buy a car.

- Drunk people.

- Anyone without the local driver’s license.

- People who choose to not drive for health, environmental and/or traffic jam reasons.

What factors need to be considered in making multimodal transport attractive?

- Location and conditions of public transport stations and stops

- Benches and shelters at stops

- Safe pedestrian sidewalks and bicycle lanes connected to public transport

- Crosswalks, pedestrian signals, and sufficient crossing times

- Capacity to carry bicycles on public transport vehicles

- Accessibility and capacity for wheelchairs

- Accessibility and safety for blind passengers

- Parking for bicycles and vehicles at stations and stops

- Availability of bicycle-sharing services

- Coordination of public transport systems

- Informational and navigational support

- Availability of real-time occupancy data

What is route optimisation?

Where can the data for route optimisation algorithms be obtained?

- Satellite data

- Public transport network information

- IoT sensor data

- Mobile data

- Weather forecasts

- Traffic forecasts

What is Pareto efficiency or optimality?

What is multimodal planning?

It is transport and land use planning which considers the differing capabilities of different transport modes and land use factors that affect accessibility including availability, speed, density, costs, limitations and appropriate uses. One of the best ways for planners to do multimodal planning is to experience the multimodal transport themselves.